Download Minus the Bear, Champaign IL, 27 May 2004.

Filed under: Writing | Tags: Mission Accomplished, Short Story, The Ballad of the First Mistake, Wasps

It happened before I knew it. One day, nothing. The next day, wasps, en masse, are bleeding from the dark of the shed and into the bright of day. I’m taking care of some yard work and sweating a little bit when I first see them, carving nonsensical flight patterns into the afternoon’s humidity. I hate, despise, loathe wasps. My childhood is punctuated by painful memories of painful stings – riveting moments of pin-pricked melodrama that haunt me into adulthood. Wasps are sonsofsbitches, I really believe that.

I’m angry, suddenly. I don’t need immediate access to the shed but I decide to take immediate action. I’m roused into a frenetic and singular inferno of resolution: these motherfuckers are going down.

I’m a strange man when it comes to action. Inspiration strikes me quickly and pointedly. That’s just how I’ve always been. I can’t see point of patience. I get antsy, you know? I don’t always take the time to think things through. Some people say I’m a hot head. Fuck those guys, though.

Anyway, here’s my problem: my can of Raid is in the very shed that the offending wasps have taken over. It’s a cruel, but simple irony. Definitive killing requires forethought. Efficiency is mistress that undresses only for those anticipatory, calculating minds. Messy, slow burning debacles, however, are the children of men like me, whimsical beings with limited foresight and above average hand-eye coordination.

Quickly, and with razor sharp efficacy, the answer to the problem at hand materializes, literally rising from the earth into my admittedly limited cognizance: gasoline, the majestic giver and taker of life. These wasps will feel a petroleum rain and then, nothing. My mind is racing and I’ve got a taste for slaughter, the wholesale extermination of an entire colony, an entire way of life. I ponder things and feel, fleetingly, tyrannical: is this what power, true power, feels like?

I move towards the garage where I keep a gallon of gasoline for the lawn mower. I unscrew the top and emerge, like my enemy, from the shade of the garage into the sunny afternoon. My pace is so quick, so undeniably determined that I’m splashing gas all over my forearms. But I don’t care. I’m floating on testosterone, flying high. I’m the king, baby. I’m in it to win it and I don’t plan on losing. I lust for the taste of victory and for the raw freedom of annihilation. I fall into it.

When I’m about a foot away from the shed’s entrance, my breath quickens with anticipation. I flick the metal door latch upwards and use my shoulder to burst into the shed. Glancing quickly around the small structure, I see the large hive, in all its looming iniquity, nestled between the bottom of the wall and the four-by-four which frames the corner. The hive is a massive structure of wood fibers bonded by insect saliva. Throughout the shed, wasps swirl, dancing with each other in protracted, nonsensical rhythm. The atmosphere is intense.

Unprepared for such discovery, I make a calculated and strategic retreat. How did a hive of such magnitude develop under my watchful eyes? How did it become so complex, so developed? I feel foolish and out of touch with the simplest of realities, the fact that my backyard, my small, sad claim to sovereignty, has been tarnished in the slightest of ways. I allowed it, I am to blame.

These thoughts spurn me into a humming force of spite and anger. I will salt their reality, these wasps, I will take their lives. I collect my thoughts and fashion my strategy. What it lacks in framework it compensates for with emotion. I ache for victory. I shift the gas can into my left hand and charge back into the shed. I strike with immediacy and drown the hive with upwards of a gallon of gasoline.

The smell of unleaded fuel saturates the air. Luxurious fumes. Success. It is a heavy and wondrous smell and I feel light-headed and proud. The hive is quiet, save a few straggling soldiers knocking about in the trusses above my head. I did it. I won. I have erased a scourge from the earth; I have done my part.

Then, everything changes.

The slightly intoxicating scent of gas is supplanted by the domineering omnipresence of fire in the air. I turn to see voluminous black smoke billowing from the shed. I run towards the shed and rip off my shirt. I beat down on the flames but its useless. I’m useless. The flames are whipping in agitated waves of heat and smoke and it’s not long before the entire shed and the adjacent house – my house – is consumed in a writhing disaster. It’s a mess, all of it.

The wasps have won and I have failed, miserably and completely. I take only a limited enjoyment at their destruction; it has cost me dearly. Most likely, I’ve burnt my son’s cat to a spectacular crisp. Most likely, we’re moving into the trailer park on the east side of town. Few people have failed in the manner and function of this failure.

In the distance, I can hear the distant echoing ring of sirens as they flood the neighborhood. From far away, they sound like mechanical voices, laughing shrilly at me, announcing my failure. They’re too late, anyway. I feel stupid and helpless.

I’m totally numb but I know the world is buzzing with kinetic energy. The firemen are arriving, running towards me, towards the inferno. They shout: is anyone inside? And I answer; no, nothing is inside. Well, maybe my kid’s cat, but I’m not sure. The firefighters hit the blaze with water. By that time, there’s nothing left to save. They know this, I know this, everyone knows it. But to not make an effort, we all agree, would merely extenuate the already welling tragedy.

When its done, the house looks menacing. Everything is black and burnt. Foreign, somehow. What used to be my house is now a hill of ash, a half burned mattress and a lazy boy armchair. That’s all that’s left.

The fireman pack up their gear into their grumbling trucks and ride off into the settling twilight. I’m standing there, too afraid to think about what I’ve just done. The short version of the long story is that I’ve got no one to blame but myself. It’s been a pattern, throughout my life. I don’t think things through. Never have, unfortunately. I can remember when I was in grade school and I got busted for stealing cartons of chocolate milk and exploding them against the cafeteria wall. My punishment? Writing, precisely one thousand and five hundred times, I will think before I act.

Filed under: Music | Tags: Airports, Ambient, Brian Eno, Downloads, Holy Shit, Music For Airports

Download Brian Eno’s “Ambient 1: Music for Airports.”

30,000 feet in the air. Suspended by technology and – unthinkably – steel and plastic and impenetrable glass. Crane your neck, look down. Through the emulsified strands of wispy cirrus clouds set against a backdrop of unimaginable blue – do you see it? The contours of the earth, the microscopically nondescript rug of green and brown, the checker board patterns of agriculture and history. Dots of towns and places. Places with doctors, preachers, murderers, mechanics. Do you see it? Do you really see it? Your eyes tell you that its unlimited. Your brain tells you its not. The world stretches out lazily before you with intimidating beauty. 30,000 feet in the air, time and sound are meaningless. A ceiling of azure masks the black above. You’re apart from everything. Can you feel it?

Download Neutral Milk Hotel, San Francisco CA, 4 April 1998.

Filed under: Writing | Tags: Despondency, How to Fix What Is Broken, Internet Dating for Dummies, Short Story, Tom Waits, Writing

Experience is an awkward concept. It’s shapeless, enigmatic, impossible to define or corral. In real time, the events that lodge themselves in the rudiment of the human psyche often seem unreal. Reaction is primal. Instinctive. Digestion is an afterthought, a malicious and emaciated human conception. Sometimes the really important things in life, the scattered and momentary circumstances that emerge under the guise of routine, don’t seem substantial until hours, days, months, years after the fact.

The first real memory I have of manhood or otherwise occurred in a dive bar when I was 23. It didn’t strike me as important until much later. But as in all stories of youth dissolved – conquered, demoralized, browbeaten – I grew up. Within this ubiquitously-labeled process of summiting the icy peak of adulthood, I realized several things, simple, oft-passed over realities that high definition television, beautiful women, and the smell of spring in the air beg us forget.

We all grow up, grow old, become marginalized. We smell the arresting and barbaric storm that accumulates on the horizon. In it, our fate is revealed through a show of fantastic and blinding electricity. It is brilliant and heartbreaking. We draw the line between black and white and spit the grayness of adolescence into the air. Because it is here, when we shed our youthful uprightness for the comfort found in the armor of maturity, that the end exerts itself and, like a cancer, steadfastly eats away at away at the former clarity of optimism. Growing old isn’t, in itself, remarkable. It’s not special or exciting or hermetically pointed. You’re born, you grow up, old, and die. Predestination, baby. Accept it or run from it, it’s your choice. Que sera sera.

But my pedestrian musings on the subjects of life and death are trivial and unnecessary. They lack the brawn and the relevance of my story – or, for that matter, any story. So, we cut to the chase:

I was 23 years old and at a point in my life in which my fledgling ideologies were lodged between the granular realities of uncertainty and fragmented mediocrity. I was metaphorically adrift in a sea of alternating cerulean and choleric blues. Violent storms would give way to momentary yet manumissional bursts of sunlight. The girl who I had hoped to spend eternity with had just left me, citing my unadulterated bitterness and romantic cynicism as the cause. She left me devastated and chain smoking, holed up in the darkness of my room, cursing her as a tyrannical cunt. I was angry, I was sad, I was fucking pathetic. I began to look at life in terms of cause and effect, a failed experiment in pragmatic utilitarianism. Like I said, fucking pathetic.

It was a largely nondescript Thursday night in the middle of February. Now, I hate February as much as living, breathing entity can possibility hate a simple facet of the Julian calendar system. People tell me that I should hate rapists, murderers, dictators, and terrorists. And I do. But I really, really, really fucking hate February. Life loses its velocity, its crispness, its poignancy. The all too early abetment of daylight acts a serviceable yet poor camouflage for the doleful bleakness of winter. Spring is on the horizon, but too far away to be tasted or touched or smelled. The skeptic – the cynic – inside of me tells me that if I can’t wrap my fingers around it or put it in my mouth, it’s not real. And if it’s not real, what’s the point of thinking about it?

So, on this particular Thursday evening, I sought refuge, for a retrospectively unknown reason, in a disgraceful and ramshackle tavern then known as Lady Byron’s. It was the kind of place that kept the lights low out of necessity, lest the God-fearing patrons be subjected to a floor painted with vomit and blood. The tables were stained with the sticky residue of spilled drinks and dimmed horizons. The ancient beer memorabilia, in its outdated splendor, served as a decrepit mile marker, rigidly chronicling the duration to which this particular establishment had served as a catalyst for degeneration. Oh, sweet, sweet intoxication, you sirenic mistress of escapism.

Above all, Lady Byron’s was a mirage. A shit-stained cesspool of humanity and grit that gave the illusion of freedom, but in reality, did little more than cement the fact that to be here is to be in the deepest and darkest place of the human condition, the place where hope has finally, and often tortuously, been put to rest.

In this insignificant bar in an insignificant small town in America’s Rust Belt sat, with me, two of my friends, people whose faces and personalities have now become opaquely washed away in the polluted river of time and place. In retrospect, mere acquaintances. The jukebox, burrowed snugly in the darkest of the bar’s dim corners, was, fittingly, playing lounge-era Tom Waits. Waits – and especially so during his parlor-tune days – has always been someone whom I respected. He did not see life in terms of good or bad, merely in sequences of being drunk and being alive. He did not fuck around with attachment or reverie. He existed, simply and pontifically.

So, as my friends and I sat in this bar listening to Tom Waits and conversing, undoubtedly of high-minded and eloquent things, the inexplicable came crashing down upon us. It unraveled like a story out of some sort of white trash, penthouse-ian fantasy: surreal and brutal, eloquent and smugly arousing.

Like all grand stories, it began innocuously: from the bar, directly across from the table where we sat, a woman rose and made her way towards us. She carried herself with a burlesque, albeit crestfallen, swagger. She wore her dirty blonde hair in a messy half pony tail. Life had not been kind to this woman. But irregardless of nurture, this woman was never destined for beauty. She looked to exist on a diet of cigarettes and small-mindedness and was dressed in the trashiest of attire – tapered blue jeans matched tactfully with a black leather vest and a Dallas Cowboys themed Looney Toons shirt. To even the most casual of observers it was readily apparent that this woman – a mess of booze and stupor – was a molten and tangible perfection of the white trash animal. She inched closer and, collectively, myself and my tablemates cringed. We knew it was happening and we wished it wasn’t. The violence of occurrence is a powerful, confusing matter.

Closer and closer, and closer she inched. Closer, still.

Inside, I was wishing for nothing more than for her to abandon her foray across the bar, to break off eye contact, to leave us the fuck alone. This was like an encounter between an African and a crocodile, a dangerous juxtaposition between predator and prey that would have the most disastrous of results.

She addressed us in a cackling, enigmatic tone that reeked of trailer parks and casino parking lots.

“You bbb-boys,” she slurred. “You boys ssss-seemm to be pretty lonely.” We looked at her, our faces surely pained with stress and woe. She paused and the air hung pregnant. The calm before the storm, the deafening quiet before the bomb, the silence on the other end of the phone right before you hear something really terrible, like I don’t love you anymore or your father died this morning.

In near symbiotic unison, we replied that no lady, we weren’t lonely, we don’t need or want your company, please, lady, please get the fuck out of here and leave us alone. Go back to the bar, to your life, to your catacomb of desperation. Please.

Undeterred by our alcohol inspired courage, she plodded forward, thrusting herself into that patch of dirt and blood that exists between the trenches of friend and foe.

“Look, I got sss-ssssomething that mmm-mmight interest you gggg-g-gguys,” she said. “Yyyy-you boys happen to like bbb-bblowjobs? Yyyy-you like gettin’ y-yyall’s dick sucked?”

With that, she had arrived at her destination. Here, she threw the knockout punch, the mother of all propositions, the most fucking ridiculous thing I have ever heard or ever hope to hear. She delivered it through an anxiously clenched jaw, her hot, stale breath whistling through her archeologically ignored teeth.

“I’ll suck yyy-yyer dicks ff-for twenty bucks. All ttt-three. Twenty bucks.” She stood above us, looking proud and content. Accomplished, somehow.

She then delivered a visual of the suggestion, opening her mouth wide, hands wrapped around an imagined shaft as if fellatio was, in some way, an abstract concept.

The comment cut through the night with the potency of assassination. It commanded response, demanded to be confronted, defied both plausibility and rationale. Her comment, her demeanor, and her ghastly smirk were all delivered with the finesse and sensitivity of rape. Her world invaded ours. The situation was volcanic, she erupting with a vesuevian current of scum and vice and we, the innocent and naïve townspeople below, running and begging for our lives. It was to no avail. I struggled to answer her. Her suggestion was beyond ludicrous. It was indecent, a comment of impenetrable dilapidation.

In a strangled voice, heavy with a mixture of pity and acrimony, I responded that no, you fucking pig, I’d rather die than let you within spitting distance of my exposed, aroused member. For good measure, I called her a bitch, a cunt, a hog. An animal. I yelled these obscenities into the night, awestruck at my own ferocity. Everything was so unfair.

She took the comment with grace and, surprisingly, a simple sense of level headedness.

“Fff-fuck yyyy-you guys, then,” she said, her yellow eyes darting and glaring at us. Her lips pursed into a growl. “Yyyy-you think you’re better than mmm-me?”

She paused for a brief second, as if confused by the rejection, only to then answer her own rhetorical question.

“Bbbb-because you’re ffff-ffffucking not. You aaaren’t better than me. Yyyy-you’re not.” She put her hands on her hips and repeated with great purpose “Yyyy-you’re nnnn-nnot better than mm-me.”

And then, as she turned to retreat to her bar stool, she was felled by a blow with a fundamentally monumental importance. A blubbery right fist, thrown with accuracy and meaning, hit her face with a meaty thump. She let out a harrowing sound, a vociferate bluster of a deep and trembling viscosity, fueled by beer and disaster and public assistance monies. She grabbed the left side of her face and feigned death. Above her stood a man, thick with brute sexuality and imbedded sourness. He wore his tattoos with a mural-like pride. This was not a man to fuck with, not a man to look, not man to acknowledge or celebrate or even consider human. He was beast, an animal, a fucking firebrand of carnality and laziness. Then, he turned. His eyes met mine.

“Sorry, guys, my wife’s a fucking whore. Lemme buy you a drink.” He turned to the bar, and yelled “three Millers,” before turning to look disgustedly at his wife sprawled on the floor.

And that was it. He turned and kicked softly her in the ribs. His disposition was that of complacent normalcy. Like episodes such as were a regular occurrence, a simple marital disagreement that was a tolerated annoyance. She looked up as he walked back to his bar stool, unleashing an erstwhile flow of vulgarity at no on in particular.

Pitifully, then, she picked herself up and walked across the now silent bar and sat in the barstool next to her husband. He ordered her a beer and told her to put it on her face and she complied under his watchful eye. And so they sat: He, the author of her welling bruises and she, the terminal skank. Good and bad, right and wrong, decency and vulgarity – these values had no place in either’s hearts or minds. These people simply existed, devoid of ideology, morality, and poignancy. They were real only because of their bones and flesh and blood and hair. Reluctantly, the bar’s patrons returned to their conversations and life pushed onward. We finished our beers and disappeared into the snowy night.

Ten years later, my broken heart is mended and I live a good, safe life. I live in a house, drive a car, have a job and a wife and a kid on the way. I live the suburban life: I look forward to weekends and cookouts and waking up every morning wrapped around a beautiful woman. I’m at peace with who I am and who I was and I have a pretty clear idea of who I want to be. My life, finally, is what I always wanted it to be.

In retrospect and revision, however, I look back on that night often. It haunts me, it makes me laugh, and it seems to have some sort of deep-rooted importance to who I once was and who I became. The night was the antithesis of Rockwellian, a moment of wholesale sleaze and despondency. I’ve always wondered what drives human beings to such dark places, metaphorical battlefields that torture the mind and destroy the body. I still can’t figure it out. Deep down, I don’t think I really want to. I don’t want to know where all that pain and bitterness and unimportance comes from. Desperation of that velocity must come from a place that is both bottomless and caliginous, a place that is cloudy with frailty and bereavement. It operates like a vector, greedily consuming the good in people, leaving the upright hobbled and crippled with weight. I don’t want to know that kind life. And, that’s important, or at least so to my small, simple mind. Because if you know what you don’t want, well, you’re one step closer to figuring out what you do want. And that’s what we’re all trying to do, right?

Filed under: Music | Tags: 1992, Downloads, Jawbreaker, Seaweed, Sub Pop Records, Superchunk, Tacoma WA, Weak

The Gods of retropsection don’t kiss and tell. The precipice of seminality and the phenomena of the near miss are separated only slightly. While Jawbreaker and Superchunk are remembered in a bronzed glory, I can’t help but think this album never fully gets its due. Alas, I’m not the arbiter of taste I hope to be, rather a small, sometimes disheveled man with a taste for malnourished reverie.

You eat. You sleep. You dream about drowning, redemption.You wish you lived thousands of miles away, in a place without such discomforting levity. Sometimes, you wish you weren’t you. Or, at least, you wish you weren’t defined by your cheap clothing and the bags under your eyes. You wish you didn’t live a life full of coffee and cigarettes.

But, you eat. You sleep. The days drag on late into the night. Eventually, albeit slowly, you lose your ability to sleep. You lose your ability to believe. In yourself, in anything. Somewhere, somehow, life became confusing. The horizon that is your future has become increasingly dark – clouded with trepidation and uncertainty. Where do you go? What do you do? People tell you to hold on, that things might not be good now but in the future, they will be. The problem is that you can’t imagine a time when things will be good, when you will feel whole or relevant. You can’t imaging that things will improve. You can’t even remember at what point things started to go wrong.

So, you try to eat. You try to sleep. You end up tossing and turning in your bed. You wear your insomnia on your shoulder. You feel empty, hollow. You listen to sad music in an effort to feel better. But you don’t. You feel worse. You lose track of time, you lose track of yourself, and then you stop caring. You think about things you shouldn’t. Afterwards, you feel guilty, selfish, and insincere.

You try to eat. You try to sleep.

It’s a life.

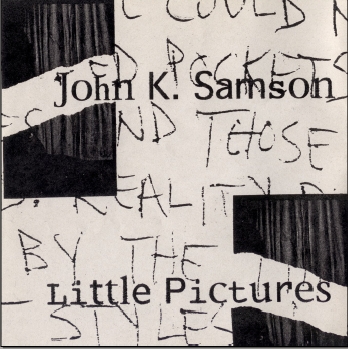

Filed under: Music | Tags: Downloads, Little Pictures, Music, Propagandhi, The Weakerthans, Tom Waits, Winnepeg

Download John K. Sampsons “Little Pictures.”

Side Projects, omg. There’s something fundamentally interesting about the concept of a “side project.” The implication is, of course, that these projects take a back seat to an artist’s primary work. But if art is anchored to dedication, and dedication is anchored to the time continuum, then what is a side project? A release from the release? A harbinger of a soon-to-be altered future? Drivel? I’m not sure. I’ve always viewed the side-projects of my favorite of my artists to be something along the lines of bonus material: some of it might be wholly spectacular but, mostly, it’s little more than a mish-mash of potential punctuated by intermittent flashes of brilliance.

John K. Sampson’s “Little Pictures” accentuates such thought in remarkable fashion. Released in 1995 by Winnepeg’s G7 Welcoming Committee Records, the EP is composed of songs that Sampson wrote while serving as bass player for the surrealist/leftist/post-modern situationist punk band, Propagandhi. In Sampson’s case, “Little Pictures” served as a predecessor to his cerebral rock musings later popularized by The Weakerthans.

In its totality, “Little Pictures” is neither good nor bad nor mediocre. For everything that it’s not, however, “Little Pictures” contains a peculiar sort of depth, a half-actualized vision that – sometimes frustratingly – never fully emerges. At times, however, Sampson’s lyrics reach stunning heights, such as on the track Maryland Bridge, in which he sternly waxes: “I can be J Edger Hoover and you be JFK/As power hungry egocentrics, we’ll paper fight the night away.” In contrast, tracks such as Sunday Afternoon and Sympathetic Smile ramble and stumble along, searching for purpose without fruition.

Don’t misunderstand me, however: “Little Pictures” is worth listening to. And, for some, re-listening to. While the EP certainly doesn’t have the reach of either Sampson-era Propagandi or The Weakerthans, it does have subtle sense of imprecise self-awareness that flickers endearingly and, at times, meaningfully.

Tom Waits, omg. Individuality is stripped for the sense of collectivism. For better or worse, a collage emerges, a real time visualization of associated elements. Somehow, the product is a touching depiction of sand and water and hectic industry.

Jim Belaine was feeling it. He was swinging the bat miraculously, his fielding was phenomenal, his confidence was fully and rigidly aroused. He felt like someone else, someone tagged for greatness.

Sure, this was Low A ball. And, sure, a big crowd was four thousand people. But Jim Belaine was riding high. He’d never felt so violently in control when swinging the bat. It felt like a perfect extension of his body, an extra appendage made of crafted wood. On the short, anticipatory walk from the on-deck circle to the batter‘s box, Belaine knew he was going to hit the ball and hit it hard. He could feel it, a tingling sensation rising from his torso into his neck, through his jowls, and into the night sky. His energy was kinetic.

His defensive prowess, too, had been gloriously increased. He saw the field in a new light, a sharply defined grid of cause and effect, risk and reward. Jim Belaine caught balls that Jim Belaine had never before caught. He had stretched and ranged to his left and right with vertical purpose and crisp efficiency. This was the life. Jim Beliane knew he was on the way up.

The good life, however, would prove fleeting to Jim Belaine. He had a career August and then, without reverie, the season ended. As he left the ball park the last time, he hoped that next year would be better. He believed – really and truly – as if he had crossed the line of demarcation between marginality and legitimacy.

On the fifteen hour roadtrip home, however, Jim Belaine fell asleep at the wheel and barreled his rented sedan headlong into a dark ravine just outside of Heyburn, Idaho. There, he would sit paralyzed in the driver’s seat and feel the life drain out of him.

We don’t talk anymore, you know? Not like we used to. She seems distant. I’m probably distant, too. Who knows why it’s like this. 31 years is a long time. I look back at the past 31 years – 34 if you count before we were married – and it’s like I can’t imagine myself without her. She’s part of me. So it’s hard, not talking. We say the same empty things to each other every day, we talk about the weather or the war on TV. She asks me for help when she’s doing her crossword puzzle every morning and I try to oblige. I peck her on the cheek on my way out the door every morning. The American dream, right? But we don’t really seem to say anything to each other. I don’t get it. I wish I did, I really wish I got it. But I don’t and it bothers me.

Maybe we’re just getting old. Maybe this is part of the entire process. Find someone you love. Get married. Have kids. Raise those kids. Watch them grow up and leave, go to college and then move somewhere 3,000 miles away. Watch them not need you anymore and pretend to be happy about it. Realize that you’re old and largely useless and you’ve nothing to look forward to except grandchildren and maybe death.

The problem is, you see, she and I don’t talk about these things. I miss talking to her. I remember on our honeymoon – we went to Hawaii – sitting on the beach next to her and talking. Really talking. Talking about love, books, children, the way the south pacific is beautiful and alive and like nothing we’d ever seen before.

I remember bringing her home after we – well, she- had our first kid. We’ve got this tiny little baby, this helpless little human that’s fat and pink and a mixture of beautiful and ugly. I’m holding him and sitting in the living room. She’s sitting next to me. He won’t stop crying. I don’t know what to do, what to say. He just won’t stop crying. And she just keeps saying, it’s alright, it’s alright, it’s alright. It sent chills up my spine, you know? A wife, a kid, a house. I’m a father, she’s a mother. Unbelievable in a completely believable way. Later that night, when the baby had finally stopped crying and fallen asleep, I remember talking to her. Really talking. We were laying in bed, next to each other. I had my arms wrapped around her and I told her that I’d never been this happy. She told me that besides being a little sore, she was happy, too. Happier than she’d ever thought she’d be.

We had another kid. We got a bigger house. Life became about working overtime to buy a nicer car and refinish the basement, PTA meetings, little kid’s basketball games, all that shit. I liked it. We were always busy, and it was good that way. Life went by so fast. Now that I think about it, maybe too fast. We never got a chance to just sit down and breathe. You know, hold hands and talk. Really talk.

I don’t know how long it’s been since we last talked about anything. We call our son who lives on the west coast – I’m always on the line in the kitchen, she’s always on the line in the bedroom – and we listen to him, tell him to eat well, tell him that we love him, all that parental-type shit, even though we know he doesn’t need it from us anymore. He’s grown up, you know? We did a good job raising him, all things considered, and he just doesn’t need us anymore. After we hang up, we say the same things to each other, like I hope’s he doing alright, he sounds good. You know, meaningless, hollow stuff like that.

We don’t talk to our other son because he’s dead. He died from cancer when he was 17. It was sad. But I won’t, can’t use that as a crutch to explain why she and I don’t talk anymore. It was hard when it happened, but it’s been 14 years. 14 years is a long time. I’m sad that it happened, she’s sad that it happened. We’ll both always be sad that it happened. But even when it was happening, even when we knew that there was no hope, no way out, we still talked. We talked about being young and hopeless and having to stare your own mortality in the eyes. We talked about how dark that must be. We talked about broken hearts, how we couldn’t believe that this was happening that we couldn’t understand why this was happening, and how we wished more than anything that this wasn’t happening. I remember the day of the funeral. It was raining. The funeral was huge. It seemed like all the people from his high school were there. Son #1, the one with cancer, told me this would happen. He told me that he probably wouldn’t like half the people there. He said he was the cause-celeb of Big Miami High School. He said that it was sort of like a bandwagon thing. Let’s rally around the kid with cancer. God, that kid was smart. I miss him, I really do. I wish I got the chance to see him grow up. He also told me that he played the cancer card to get laid. I patted him on the back. I was happy for him, you know? No one wants to die a virgin.

Anyway, we’re at his funeral. It’s raining outside, a warm, gray spring day. The perfect day for a funeral, really. All these people with somber looks on their faces. Everywhere you look, people looking downcast and downtrodden. I didn’t know a lot of the people there. I guess I was glad they came, though. I’m sitting there, in the front row of this cavernous church. My wife is crying and I’m trying as hard as I can not to. I grab her around the shoulders and tell her that I love her. She doesn’t respond. I feel helpless as I listen to her sobs punctuate the air and bounce resoundingly off the church’s stained glass windows. It feels weird, you know? Like I’m in this church surrounded by literally everyone I know in this world – and a lot of people I don’t – and I feel more alone and empty than I’ve ever felt in my life.

So this young priest guy with a crew cut gets up in front of everyone and starts talking. About God and plans and joyous reunions in heaven. Typical bullshit, you know? And all I can think about is when we brought him home from the hospital and he wouldn’t stop crying. And how my wife patted him on the head and just kept repeating it’s alright, it’s alright, it’s alright. I still get goose bumps when I think about it.

And then I think about my life now. About how sad I am. I mean, the love of my life, the mother of my children, my better half is sitting next to me and crying. She has just lost her son, our first born. She’s crying uncontrollably and I just want to somehow tell her that it’s alright. But I can’t, I just can’t. I realize this and it kills me. But what can I do?

After the funeral, after that day, life was rough. We had a kid and ourselves to take care of, we had a house and bills and jobs to obsess over. We still talked, though. We went to meetings together, where professionals told us how to deal with grief. About how it seemed dark right now but just over the horizon, there was sunshine and happiness. A bunch of flowery, metaphorical nonsense. I never really bought into it, you know? If these people were as smart and as worthwhile as they claimed to be, why in the hell do they have to peddle their services to the hopelessly inconsolable? I mean, speaking from experience, the grief-stricken pretty easy-going consumers. Case in point, right after my son died, I bought a new car. Not because I wanted a new car or needed a new car, but because I thought maybe it would make me feel alive again. You know, go out into the world and spend a lot of money on something you don’t need. But it didn’t really work. I just felt like a guy with a new car and a dead kid.

But, as usually is the case, life moved on. And we still talked, her and I. We got through it the best we could, you know? I tried my best and she tried her best. We went out to dinner a lot, took some vacations. Started having sex again. We tried to replace the gaping hole in both our hearts by loving each other even more. It worked for awhile.

When our other son moved out to go to college, it was a shock. Not the way that son #1’s departure was a shock, but still, a shock. The house felt so empty. The funny thing is, the more time we had together, the less we talked. Life started to become so routine. So goddamn routine. We still went out to dinner. We rarely had sex, though. Menopause or some lady issue like that. I never really made her explain it to me, you know? I feel like she earned the right to no longer have sex with me, after more than 25 years of enduring my awkward lovemaking and pale, sweating body. Plus, we’re getting old, and frankly, erections don’t come to me like they used to. Who’d of thought? I remember being 18 and I having to tuck the goddamn thing into my belt on account of the good-looking blond that sat across from me in freshman English.

Anyway, we got old. Gradually, and then suddenly, it become hard to talk to each other. I guess I just never really had anything to say. And she didn’t either. She knows I love her more than anything in the world and vice-versa. Maybe when you’ve been together for so long, you just don’t have anything left to say. I don’t know. We’ve been through a lot in our lives. Being young and dirt poor, fighting and scratching to make a place in this world. Making it, starting a family. Having kids and loving those kids immeasurably. Watching our first born pass away, watching our second born become a man. Watching ourselves get old and grey and slightly useless. We went through all of this together. I mean, I know what she’s thinking and she knows what I’m thinking. What’s there to say? But, I wish we had something to say, I really do.

Last week, it was the 16th anniversary of son #1 dying. Like always, we go to this giant, mega-graveyard on the west side of town where he’s buried. This place is something else. It’s like 45 acres of dead bodies. The mausoleum is this contemporary slash brooding marble temple that they built 10 or so years ago. I don’t get it, honestly. Another thing I don’t get about this graveyard is the monthly newsletter they send. I mean, Jesus Christ. I’m not really concerned about the monthly happenings at the White Crane Cemetery. I called once, and told them to stop sending the goddamn things. But they still come.

So, we’re at this cemetery. She brought some flowers. She always brings flowers. I guess to say that even though our son has been dead for a long time, he’s still loved. I personally wouldn’t bring flowers, but I don’t blame her for bringing flowers. It’s a nice gesture, you know? We stand there for awhile. She cries. I put my arm around her shoulder. I’ve been done crying for a long time. It’s a blue sky day, bright and warm and its spring and you can hear birds in the trees and the air smells nice. And I start thinking, thinking about how we don’t really talk anymore. It’s killing me, it really is. I’m funny like that. I guess I knew for a long time that we stopped talking but I never really thought about it until that moment. It immediately bothered me. Why don’t we talk anymore? Really talk? I wish I knew. Really, I do.

We stand by the grave for a little while and then get into the car. The drive home is pretty much silent until she says that she’s hungry. I agree with her, I’m hungry too. We stop at this little restaurant by our house. We eat here a lot, I guess. The food is ok and it’s cheap and clean, so I don’t mind it. After we eat, we drink coffee- decaf for her – and I pay the bill and we go home. I sit down on the couch and watch television. A basketball game is on. Pro ball, Denver at Los Angeles. I don’t really care for either of these teams as I’m more of a Eastern Conference type of guy. But still, I watch. She is in the kitchen, doing something. I hear her banging around.

Later that night, we’re laying in bed. My leg is crossed over hers. I’m still annoyed that we don’t talk, really talk, like we used to. I’m trying really hard to think of why we don’t talk anymore, trying to come up with a good explanation. I can’t. I know that some people would take the easy route and blame it on the dead son or the other son that lives 3,000 miles away and won’t give us the time of day besides a phone call every couple weeks. But I’m not those people. Yeah, we’re old. But I can’t imagine myself without her. Like I said, she’s a part of me. And she’s smart. I’ve always loved that about her, how smart she is. She used to say things that would just blow me away. It kills me that we don’t talk anymore.

I don’t sleep well that night or any of the nights for the rest of the week. The whole “we don’t talk anymore” thing is really bothering me. It’s making me look at the past 34 years in a way I’d never thought I’d look at them, you know? I’m really and totally sad, it’s making me go crazy on the inside. So finally, after a week of not sleeping and not eating, I get the courage to talk to her about it. This is big, this is important. This could be the most important conversation that I have before I die. It’s that important. I miss talking to her, I really do. It eats me up that we don’t talk. What happened?

We’re sitting at the kitchen table, reading different sections of the newspaper. I tell her that there’s something I want to talk to her about. It’s funny, you know? I’m trying to have our first real conversation in God knows how long and I have to start it out with the phrase “there’s something we’ve got to talk about.” Like I’m 15 years old . She looks up at me. I start talking. I start from the beginning, how we never really talk. How it bothers me. How I remember being so young and so in love. About our honeymoon and the magic blue of the endless pacific. About bringing son #1 home and how he wouldn’t stop crying and she just kept saying that its alright, its alright, its alright. About funerals and emptiness and wanting to just start talking, really talking, again. And suddenly, I’m crying. A 55 year old man, sitting at the kitchen table, crying. And I can’t stop. I haven’t cried in years. I wish I wasn’t crying now. I’m talking in circles, not really making any sense. I’ve got a lot of things to say, but I’m not saying anything. I’ve bottled all this real talk up inside for so long and now its just pouring out me. So I’m talking and crying and not making any sense whatsoever. And I look across the table and see that she’s crying, too. This makes me cry more. I think she understands, I hope she understands, really, I do.

And then she starts talking. It’s beautiful, in a way. We’re both crying and talking about the past 31 – or 34 if you count before we were married – years. And neither of us are really saying anything, but we both understand, I think. I reach across the table and grab her wrist and look into the familiarity of her eyes. It’s comfortable, knowing someone as well as I know her.

Then she stands up and walks over to me. She stands behind me and reaches her arms down around my chest and whispers in my ear that it’s alright, it’s alright.

It’s alright, she says, over and over.